Distinguished Historian uniquely tells the story of The Turning Point

Friederike Baer a frequent speaker on Saratoga with Hessians presentation

Dr. Friederike Baer spoke at the 3rd Women in War Symposium on Saturday May 4, 2024. The prestigious event featured a panel of experts on Women in the Revolutionary War.

Her address describes the experience of Saratoga, "With the Battle of Saratoga our Misfortunes began, Friederike Riedesel in the War for American Independence".

Dr. Baer has spoken recently at the Saratoga Battlefield and at important conferences throughout the United States. Her book Hessians was awarded the 2023 Society of the Cincinnati Prize and most recently was a Finalist for the American Battlefield Trust Inaugural Military History Book. Other awards include the 2022 American Revolution Round Table of Philadelphia's Book Award, and Distinguished Historian by The Marshall House Inc., preserving the site of the Baroness’s immersion in combat.

Professor Baer continues to research in preparation of further publication. Her website range of Gen. John Burgoyne’s last stand of the Battles of Saratoga, now site of the Saratoga Monument.is https://friederikebaer.com/ .

Dr Baer continues to add valuable research

Dr Friederike Baer's research continues to produce valuable findings

On topics from Gen John Burgoyne to Gen Riedsel and the Convention Army, see friederikebaer.com.

As we approach 2027 - the 250th anniversary of the Saratoga battles - renewed activity is occurring at the Saratoga Battlefield and the region.

Baroness Riedesel's Shelter

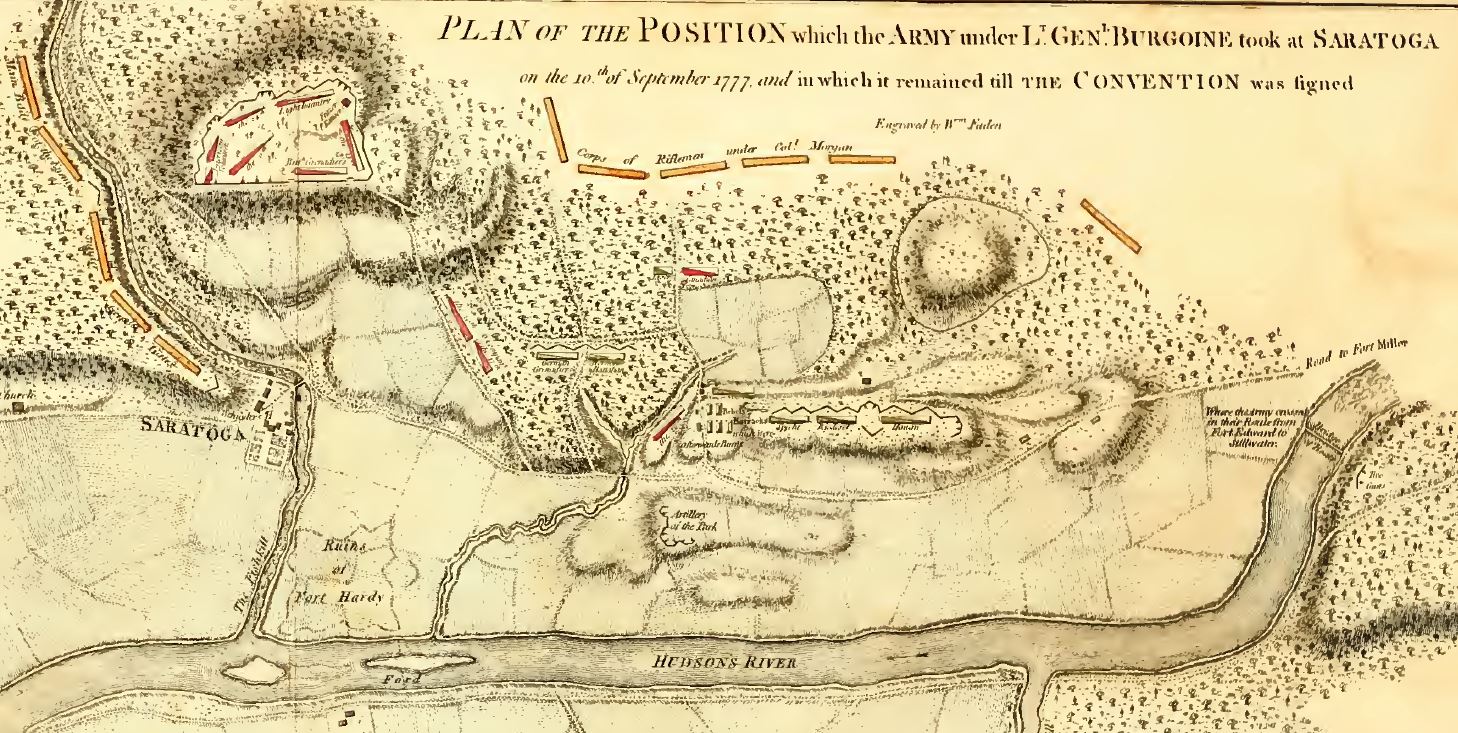

Following his defeat at the Second Battle of Saratoga, General Burgoyne reluctantly and hesitatingly determined to escape with what remained of his army to Canada in the hope that the campaign might be resumed in the next year.

However, heavy incessant rains bogged down his artillery and baggage train on the retreat north. Pursuit by General Gates’ American army forced Burgoyne to consolidate his forces at Saratoga to better withstand enemy attacks.

On October 10, 1777 he requisitioned the Lansing farmhouse (now The Marshall House) for use as a hospital for wounded officers and men and as a refuge for the wives and children who accompanied their officer husbands, such as Lady Harriet Acland and Lady Anne Reynell. Most notable of those so sheltered, was the Baroness Frederika Charlotte Louise Riedesel and her three young daughters, Augusta, Frederika and Caroline.

Madame Riedesel’s husband was Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel who commanded the German auxiliary troops attached to the British army. It is to this remarkable lady that we owe not only so much of our knowledge of the house but, too, of the personalities of Burgoyne, his officers and of the deplorable state of his ill-fated retreat.

In her celebrated diary and letters, elegantly yet simply written, the baroness recounts her experiences, her fears and her joys. Always fearful that the worst might befall her husband, she recounts her relief when venturing out at night she sees off to the south her husband’s campfires softly illuminating the gloom.

In daytime she spots the sharpshooters watching the house from the opposite shore of the Hudson who made marks of the men who sought to fetch desperately needed water from the river because the well had gone dry.

To visualize these scenes nowadays is difficult because trees and bushes thickly cover what was then a cleared landscape. From an eminence slightly north of the Batten Kill (which flows into the Hudson opposite the house) Captain Furnival’s American artillery battery constantly menaced the house with occasional fire in the mistaken belief that the building was Burgoyne’s headquarters.

What is being described is an ample yet simple farmhouse surrounded with fields. The farm contained a few acres of good river bottom land but for the most part its uplands were largely clay punctured by shale outcrops and wetlands.

The farm perhaps probably supported a half dozen cows, a few head of sheep, some poultry, a dozen hogs and a horse or two. Because the Lansings had fled before the British onslaught it is likely that the livestock was gone and crops abandoned.

In The Lansing House section of this website the reader has been given a brief description of the house as it was at the time of the Battles of Saratoga.

It is well to note here somewhat of its present character. The arrangement of the ground floor rooms has little changed save that a partition in the north room was removed some seventy years ago and that one of the two rooms on the south side of the hall was enlarged in 1868 when the gambrel roof was replaced by a single slope roof to enlarge and brighten the upstairs rooms and add windows.

The old kitchen wing was razed at the same time and a new two storey kitchen wing attached to the southwest rear of the building. The new second floor space was divided to accommodate a farmhand or household servant. Throughout, the original post-and-beam structure has remained unchanged. The front window bays became floor-to-ceiling at the time of the 1868 elaboration.

Of particular interest are the wide white pine board floors in the original portion of The Marshall House. In the north room, now a library, the floor has never been painted. The boards are tongue-and-groove, the spaces between them et retaining some of the limed clay filler used to smooth them. In the other rooms, upstairs and down, the paint has been removed to reveal the simple beauty of the old floors.

Where the addition of 1868 joins the original structure the wide boards suddenly give way to narrower ones, a sharp demarcation. Remaining. and still in use from the time of the Battles of Saratoga, are the hinges and great lock on the front door. The delicate thumb latch and the wooden door itself in the cellar-way admitted Mrs. General Riedesel.

A rectangular panel in the present dining room ceiling, recently opened, reveals a beam shattered by an American cannonball. The dentelle mantelpiece in the south room (now the music room) remains from Lansing days. In the north room, where the floor is blood stained, are displayed two three-pound and one five-pound solid shot cannonballs, three of the eleven the baroness reports as having struck the building.

In Stone’s translation of the Baroness’ journal, he identifies a "Surgeon Jones" as the man whose leg was being amputated at the moment a cannonball torn away his other leg. Baroness Riedesel speaks of a "poor soldier," not a surgeon. No Surgeon Jones is recorded as having been in the British army at Saratoga. Stone’s error has ricocheted through subsequent accounts.

Displayed nearby are two three pound and one five pound solid shot cannonballs, three of the eleven the baroness reports as having struck the building.

Plaguing the unfortunate inhabitants was a dearth of water because the well was dry. Recently, a trace of an old well was discovered in the present driveway. There were probably others not yet found.

The cellar (where the baroness with her children, officers’ wives and wounded crowded together seeking refuge during the cannonade) retains its solid fieldstone walls and heavy joists let into the surrounding sill. Until seventy years ago the floor was earth but is now paved with large flagstones acquired when the old sidewalks in Schuylerville were lifted in favor of concrete. The space, once divided by plain vertical board walls into three rooms, is now entirely open.

Though a steam boiler and pipes serving radiators above, together with an extensive model railroad, may jar a history purist, the vastness of the cellar, its impressive hand-hewn beams and the old door through which frightened men and women rushed to safety ignite one’s imagination. Through this door, too, were carried out the dead for burial with quicklime in shallow graves hastily dug fifty yards away to the south.

For six days preceding Burgoyne’s surrender, acts brave and cowardly, kind and mean, generous and pitiful, heroic and tragic took place within the walls of this venerable house, itself the sole survivor and witness to the decisive event at Saratoga in 1777 which was the turning point of the American Revolution.