Distinguished Historian uniquely tells the story of The Turning Point

Friederike Baer a frequent speaker on Saratoga with Hessians presentation

Dr. Friederike Baer spoke at the 3rd Women in War Symposium on Saturday May 4, 2024. The prestigious event featured a panel of experts on Women in the Revolutionary War.

Her address describes the experience of Saratoga, "With the Battle of Saratoga our Misfortunes began, Friederike Riedesel in the War for American Independence".

Dr. Baer has spoken recently at the Saratoga Battlefield and at important conferences throughout the United States. Her book Hessians was awarded the 2023 Society of the Cincinnati Prize and most recently was a Finalist for the American Battlefield Trust Inaugural Military History Book. Other awards include the 2022 American Revolution Round Table of Philadelphia's Book Award, and Distinguished Historian by The Marshall House Inc., preserving the site of the Baroness’s immersion in combat.

Professor Baer continues to research in preparation of further publication. Her website range of Gen. John Burgoyne’s last stand of the Battles of Saratoga, now site of the Saratoga Monument.is https://friederikebaer.com/ .

Dr Baer continues to add valuable research

Dr Friederike Baer's research continues to produce valuable findings

On topics from Gen John Burgoyne to Gen Riedsel and the Convention Army, see friederikebaer.com.

As we approach 2027 - the 250th anniversary of the Saratoga battles - renewed activity is occurring at the Saratoga Battlefield and the region.

Bibliography

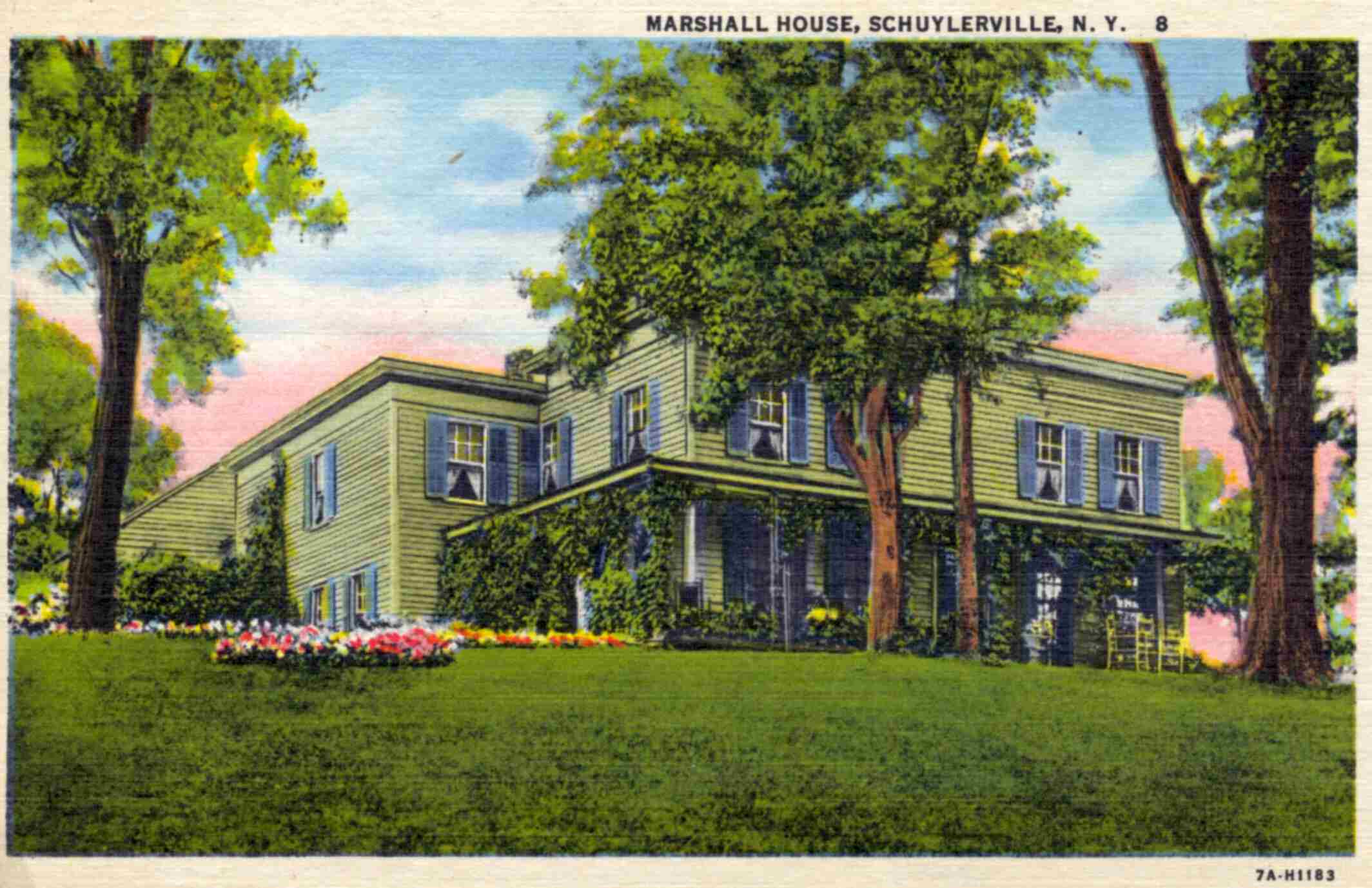

The Marshall House, in a 1920s postcard

“The Marshall house too, like the Schuyler mansion, should ultimately belong to the public. Houses like these, so closely connected with great historic events, are very rare in our country, and hence what we have left should be guarded and preserved with the most jealous care.”

John Henry Brandow, The Story of Old Saratoga and History of Schuylerville, p. 312.

Scarcely any book or article written about the Battles of Saratoga fails to describe the ordeal experienced by the Baroness Frederika Charlotte Riedesel in the cellar of what is now known as The Marshall House.

In this section, we have gathered books mostly written and published in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period of high patriotism and interest in the origin of our nation. These have been chosen because they contain reliable contemporary descriptions of The Marshall House and, here and there, the telling accounts of visitors.

Scores, maybe hundreds, of contemporary essays devoted to the decisive Battles of Saratoga devote numerous pages to the strong and attractive personality of Baroness Riedesel. Furthermore, both the brave German noblewoman and The Marshall House were characters in some fictional works, such as in Martha Finley’s Elsie Dinsmore series – a nineteenth century best-seller still sold in the millions during twentieth century’s first half - or in the work of a contemporary master of literature in English, Robert Graves.

The courage and direction that Baroness Riedesel displayed during the horrendous week she, her little daughters, other women and wounded soldiers faced as they sheltered in the crowded and wretched cellar of The Marshall House prior to the Convention of Saratoga are vividly portrayed in this collection. Several items of private interest to their writers were saved from oblivion almost by accident and are here offered.

NOTE: All page numbers are those of the actual books, not pdf’s.

BRANDOW, JOHN HENRY: The Story of Old Saratoga and History of Schuylerville, Fort Orange Press, Brandow Printing Company, Albany, N. Y., 1900 [Download]

Brandow, a “sometime pastor of the (Dutch) Reformed Church of Schuylerville” and member of the New York State Historical Association, describes the area found by the British after Burgoyne crossed the Hudson going south to his doom: “The Marshall House and one other, standing where the old parsonage of the Reformed church now is, were the only dwellings north of the creek” (p. 93).

Brandow, a “sometime pastor of the (Dutch) Reformed Church of Schuylerville” and member of the New York State Historical Association, describes the area found by the British after Burgoyne crossed the Hudson going south to his doom: “The Marshall House and one other, standing where the old parsonage of the Reformed church now is, were the only dwellings north of the creek” (p. 93).

The author mentions The Marshall House several times in his account of the days following the British army’s catastrophic defeat. Several sections are expressly dedicated to the house, “The Marshall House Cannonaded”, “The Siege” and “Baroness Riedesel Relates her Experiences” (1900 – pp. 129-130).

Pictures of note include the Baroness Riedesel (p. 141), “The original Marshall House” at it was during the Baroness and other men and women’s ordeal (p. 145) and an extremely interesting photograph of “the corner occupied by Baroness Riedesel and her children” in The Marshall House’s cellar as it appeared in the very beginning of twentieth century (p. 147).

Also, in “The Marshall House” (p. 371), Brandow discusses the history of the house and of the visit of “an old man” paid to the house in the early part of the nineteenth century.

“He had not been here since the Revolutionary war, but always wanted to come and visit that house. He said that he was the gunner that leveled the cannon that bombarded the house, that they shot several times before they got the range; finally they saw the shingles fly, and then they kept it warm for that house and its occupants, as well as other points, ‘til Burgoyne showed the white flag. On being asked why they fired on women and wounded soldiers, he replied that they supposed it to be Burgoynes’s headquarters.”

When the British army and its German auxiliaries quit their camp after the surrender treaty was signed, “the piles (of arms) reached from near the creek to the vicinity of the Marshall house” (p. 160). In “Experience of the Marshall Family” (p. 191), Brandow speaks of the presence of the Marshall family in the present area of Schuylerville and Victory since 1763 (also, pp. 243, 245, 324 and 348).

More interesting tidbits can be learnt about the Marshalls when the author portrays life in the time of the Battles of Saratoga, when “people of larger means had pewter dishes and spoons” as table furniture and Brandow points out that “Mrs. William B. Marshall of the ‘Marshall house’ has several of these plates, remnants of ‘the good old times’” (p. 251).

John H. Brandow reaches the peak of his enthusiasm in illustrating the historic importance for The Marshall House when he writes: “The Marshall house too, like the Schuyler mansion, should ultimately belong to the public. Houses like these, so closely connected with great historic events, are very rare in our country, and hence what we have left should be guarded and preserved with the most jealous care” (p. 312).

BRANDOW, JOHN HENRY: The story of Old Saratoga: The Burgoyne Campaign to Which is Added New York’s Share in the Revolution, Fort Orange Press, The Brandow Printing Company, Albany, N. Y., 1919 [Download]

In this second book, presented as a “Second Edition”, though with new contents and redactions, Brandow writes that the battery which cannonaded The Marshall House was emplaced the evening of October 9th upon a rise north of Clark’s Mills by men commanded by Captain Furnival:

In this second book, presented as a “Second Edition”, though with new contents and redactions, Brandow writes that the battery which cannonaded The Marshall House was emplaced the evening of October 9th upon a rise north of Clark’s Mills by men commanded by Captain Furnival:

“General Matoon, then a lieutenant of this company, relates that on the morning of the 10th, seeing a number of officers on the steps of a house [The Marshall house] opposite, on a hill a little north of the mouth of the Battenkill surveying our works, we opened fire on them. I leveled our guns and with such effect as to disperse them. We took the house to be their headquarters. We continued our fire till a nine or twelve pounder was brought to bear on us, and rendered our works untenable” (p. 165).

After the British army’s defeat at the second Battle of Saratoga, “the balance of the 20th British regiment, and the Germans under Riedesel, occupied the ground north of Spring street, bounded on the east by Broadway and on the west by a line running north from Dr. Webster's house and reaching toward the Marshall house. The artillery was parked on the spur of high ground east of Broadway and on the continuation of Spring street, now called Seeleyville.” (p. 166).

The cannonade of The Marshall House is related in dramatic terms in later pages (pp. 175-176), while the harsh experience of Baroness Riedesel is applauded as “a forerunner of Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton and the Red Cross” (pp. 176-184).

The preservation of the original building of the Revolutionary times is documented when Brandow tells how William B. Marshall “repaired and altered [the house] somehow about 1868” though “he, however, had the good taste to leave the lower rooms and cellar, the really interesting portions, as they were” (p. 507). New and interesting sketches of the original house and the famous cellar are included at page 179.

BROOKS, ELBRIDGE S.: The Century Book of the American Revolution, The Century Co., New York, 1897 [Download]

In the course of an excursion to Schuylerville, shadowed by the Saratoga Battle Monument above, there “flowed the Hudson, for whose possession all this blood had been shed,” the travelers “saw the home of General Schuyler on the banks of the rushing, tumbling Fish Creek; they saw the fine old Marshall house, in which Madame Reidesel [sic] and her little girls passed that dreadful day of battle, and in which the brave General Frazer died” (p. 171).

In the course of an excursion to Schuylerville, shadowed by the Saratoga Battle Monument above, there “flowed the Hudson, for whose possession all this blood had been shed,” the travelers “saw the home of General Schuyler on the banks of the rushing, tumbling Fish Creek; they saw the fine old Marshall house, in which Madame Reidesel [sic] and her little girls passed that dreadful day of battle, and in which the brave General Frazer died” (p. 171).

On p. 173 is an interesting photograph of The Marshall House, showing the fences and trees until then seen only in sketches. The caption says: “The Marshall House, Schuylerville, overlooking the Hudson. Here Madame Reidesel [sic] and her children lived during the battle, hiding the most of the time in the cellar to escape the American bombardment; and here the British General Frazer died.” The incorrect identification of The Marshall House with the place where Frazer died was not unusual at that time.

BULLARD, EDWARD F.: History of Saratoga and the Burgoyne Campaign of 1777, Waterbury & Inman, Ballston Spa, N. Y., 1876 [Download]

In an address delivered at Schuylerville, July 4th 1876, General Bullard, great-great uncle of The Marshall House’s present owner, David Bullard, denies the statement made by William L. Stone that The Marshall House had been abandoned for years (Letters and Journals relating to the War of the American Revolution and the Capture of the German Troops at Saratoga, by Mrs. General Riedesel, 1867, p. 129):

In an address delivered at Schuylerville, July 4th 1876, General Bullard, great-great uncle of The Marshall House’s present owner, David Bullard, denies the statement made by William L. Stone that The Marshall House had been abandoned for years (Letters and Journals relating to the War of the American Revolution and the Capture of the German Troops at Saratoga, by Mrs. General Riedesel, 1867, p. 129):

“The modern historian (writing in 1867) is mistaken when he says, ‘the house was allowed to fall to decay a few years since.’ On the contrary, it was merely improved by putting on a new flat roof and making the cellar still deeper. One of the old rafters and the plank of the partition, each shattered by a cannon ball, are still carefully preserved on the spot by Mrs. Marshall” (p. 14).

General Bullard adds that Mrs. Marshall, widow of William B. Marshall, “has kindly placed in my hands a gold piece, found by Samuel Marshall [William’s father] on those premises about fifty years ago, which is stamped, ‘Georgius III., Dei Gratia," with his profile on the one side, and on the other the British crown, 1776. This was evidently a coin lost by one of the officers in 1777” (p. 14).

ELLET, ELIZABETH F.: The Women of the American Revolution, Baker and Scribner, New York, 1850 [Download]

"The actions of men stand out in prominent relief, and are a safe guide in forming a judgment of them; a woman's sphere, on the other hand, is secluded, and in very few instances does her personal history, even though she may fill a conspicuous position, afford sufficient incident to throw a strong light upon her character."

"The actions of men stand out in prominent relief, and are a safe guide in forming a judgment of them; a woman's sphere, on the other hand, is secluded, and in very few instances does her personal history, even though she may fill a conspicuous position, afford sufficient incident to throw a strong light upon her character."

With her 1848 book The Women of the American Revolution, Elizabeth F. Ellet was the first writer to pay attention to the rôle of women, to their "magnanimity, fortitude, self-sacrifice, and heroism, bearing the impress of the feeling of Revolutionary days."

The historian praises the "patriotic mothers [that] nursed the infancy of freedom", but also some of the most relevant figures of the women who followed the loyalist camp, including Baroness Riedesel.

Ellet bases her story on Madame Riedesel in the first-hand account of the American General James Wilkinson, an acquaintance of the Baroness who published in English the first, though incomplete, translation of the famous journal. Elizabeth F. Ellet provides a beautiful, informal portrait of the Baroness.

"She was long remembered, with her interesting family, in Virginia, as well as in other parts of the continent. She is described as full in figure, and possessing no small share of beauty. Some of her foreign habits rendered her rather conspicuous, such as riding in boots, and in what was then called, 'the European fashion', and she was sometimes charged with carelessness in her attire." (Vol. 1, p. 142).

FINLEY, MARTHA: Elsie Yachting with the Raymonds, Dodd, Mead, and Company, New York, 1890 [Download]

Vivid description of The Marshall House – with special attention to the cellar at the close of the nineteenth century. Martha Finley (1828-1909) was an American author of numerous works who became renowned for her twenty-eight volume Elsie Dinsmore series.

Vivid description of The Marshall House – with special attention to the cellar at the close of the nineteenth century. Martha Finley (1828-1909) was an American author of numerous works who became renowned for her twenty-eight volume Elsie Dinsmore series.

In “Elsie Yachting with the Raymonds”, the characters visit Revolutionary Saratoga and “the Marshall place”, a name for The Marshall House occasionally used today by some persons, especially in the Schuylerville vicinity (p. 13-21).

“From the scenes of the fight and the surrender they drove on to the Marshall place, the Captain giving the order as they reseated themselves in the carriage.

‘The Marshall place, Papa? What about it?’ asked Max and Lulu in a breath.

‘It is a house famous for its connection with the fighting in the neighbourhood of Saratoga,’ replied the Captain.

‘It was there the Baroness Riedesel took refuge with her children on the 10th of October, 1777, about two o'clock in the afternoon, going there with her three little girls, trying to get as far from the scene of conflict as she well could.”

[…]

“Then, as they entered the cellar, [the boy who was showing The Marshall House spoke] ‘There have been some changes in the hundred years and more that have passed since that terrible time,’ he said. ‘You see there is but one partition wall now; there were two then, but one has been torn down, and the floor cemented. Otherwise the cellars are just as they were at the time of the fight; only a good deal cleaner, I suspect,’ he added, with a smile, ‘for packed as they were with women, children, and wounded officers and soldiers, there must have been a good deal of filth about, as well as bad air.’

‘They certainly are beautifully clean, light, and sweet now, køb viagra uden recept, whatever they may have been on that October day of 1777,’ the Captain said, glancing admiringly at the rows of shining milk-pans showing a tempting display of thick yellow cream, and the great fruit-bins standing ready for the coming harvest.

‘Yes, sir; to me it seems a rather inviting-looking place at present,’ returned the lad, glancing from side to side with a smile of satisfaction; ‘but I've sometimes pictured it to myself as it must have looked then,—crowded, you know, with frightened women and children, and wounded officers being constantly brought in for nursing, in agonies of pain, groaning, and perhaps screaming, begging for water, which could be got only from the river, a soldier's wife bringing a small quantity at a time.’”

GRAVES, ROBERT: Sergeant Lamb’s America, Random House, New York, 1940 [Download]

Both The Marshall House and Baroness Riedesel meet again in one of Robert Graves’ novels, the adventures of Irish Sergeant Lamb during the American Revolutionary War.

Both The Marshall House and Baroness Riedesel meet again in one of Robert Graves’ novels, the adventures of Irish Sergeant Lamb during the American Revolutionary War.

Adhering closely to actual historical events that followed Burgoyne’s defeat, Graves writes of “a building which was a principal target of the American artillery –a log-house of two storeys well advertised to them [to the Americans] as constituting our general hospital.” [The building built by Peter Lansing circa 1770 was not “a log-house” but a frame one.]

In the middle of the fierce cannonade, the author points out how “some slight colour […] was provided by Madame Riedesel’s ornamental calash which stood near the door; this pretty blue-eyed lady and her three young children having taken refuge in the cellar of the building.”

The ordeal of the besieged is displayed by Graves without forgetting the double amputation of a soldier on the ground floor. Then, Sergeant Lamb exclaims: “This was only one of many horrible happenings, of which a full Detail [sic] would turn the stomach.”

The excerpt included in this section appears in a 2014 electronic edition by RosettaBooks LLC.

HOLMES, TIMOTHY and SMITH-HOLMES, LIBBY: Saratoga. America’s Battlefield, History Press, Charlestown, S. C., 2012

On pp. 105-106 Frederika Riedesel is described, in the words of the American Col. Wilkinson, “the amiable, the accomplished and dignified baroness."

On pp. 105-106 Frederika Riedesel is described, in the words of the American Col. Wilkinson, “the amiable, the accomplished and dignified baroness."

Her children are listed as Augusta, 4 years and 7 months, Frederika, 2 years and Caroline, 10 weeks old. Other ladies traveling with the British army are also commented upon.

Pp. 113-117 the Baroness’ own verbatim account of her experiences in The Marshall House appears.

A sketch of General Philip Schuyler assisting Mrs. Riedesel and her children alight from her calash is found on p. 119.

LODGE, HENRY CABOT: The Story of the Revolution, Vol. I, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1898 [Download]

LODGE, HENRY CABOT: The Story of the Revolution, Vol. II, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1898 [Download]

Detailed sketch of The Marshall House’s cellar as it appeared at the time this book was published. “Through the door is seen the room in which Madame Riedesel and her children took refuge for six days” (Vol. I, p. 252).

Detailed sketch of The Marshall House’s cellar as it appeared at the time this book was published. “Through the door is seen the room in which Madame Riedesel and her children took refuge for six days” (Vol. I, p. 252).

LOSSING, BENSON JOHN: The Hudson, from the Wilderness to the Sea, Virtue and Yorston, New York, 1866 [Download]

After describing the beautiful scene where the Batten Kill enters the Hudson, Lossing remarks how “upon the slope opposite the mouth of the Batten-Kill is the house of Samuel Marshall, known as the Reidesel [sic] House.”

After describing the beautiful scene where the Batten Kill enters the Hudson, Lossing remarks how “upon the slope opposite the mouth of the Batten-Kill is the house of Samuel Marshall, known as the Reidesel [sic] House.”

“There, eleven years before, the writer visited an old lady, ninety-two years of age, who gave him many interesting details of the old war in that vicinity,” recalls the author before adding that witness “died at the age of ninety-six” (p. 85).

Lossing summarizes the ordeal of the Baroness and the rest of women, children and wounded soldiers in the cellar of The Marshall House, but this book is particularly relevant for its sketches of “The Reidesel [sic] house” and the “Cellar of Reidesel [sic] house.”

These sketches were later included in Stone’s 1867 translation of the Letters and Journals relating to the war of the American Revolution and the capture of the German Troops at Saratoga, by Mrs. General Riedesel.

In the volume I of The Pictorial Field-Book of The Revolution (1860), Lossing already had included two drawings for the same reason –the Marshall House previous to its 1868 renovation and its famous cellar-, though on this occasion, the author correctly spells the Baroness’ last name.

LOSSING, BENSON JOHN: The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution, Vol, I, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, 1860 [Download]

Lossing includes in his book the earliest sketches of The Marshall House and its famous cellar (p. 89) before the embellishments that several years later the Marshalls undertook though preserving the structure, rooms and cellar of the original house.

Lossing includes in his book the earliest sketches of The Marshall House and its famous cellar (p. 89) before the embellishments that several years later the Marshalls undertook though preserving the structure, rooms and cellar of the original house.

Together with these drawings, Lossing adds (p. 91) a tender recreation of General Schuyler helping the Baroness and her three little daughters alight from her celebrated calash after leaving the cellar of The Marshall House once the Convention of Saratoga was signed and the American army stopped cannonading the building that they believed enemy’s headquarters.

The author marks with a small black spot the exact place where entered the cannonball that killed “the poor soldier” whose leg was being amputated in the what is now The Marshall House’s library. Also described is the cellar as “about fifteen by thirty feet in size, and lighted and ventilated by two small windows only” [actually thirty-five by twenty-five feet, with six windows].

According to Lossing, the house “is well preserved.” “At the time of the Revolution it was owned by Peter Lansing, a relative of the chancellor of that name, and now belongs to Mr. Samuel Marshall, who has the good taste to keep up its original character”, continues the author.

“It is upon the high bank west of the road from Schuylerville to Fort Miller, pleasantly shaded in front by locusts, and fairly embowered in shrubbery and fruit trees.” Today, the three locusts depicted by Lossing both in his sketch and in his text survive vast, healthy and majestic.

LOWELL, EDWARD J.: The Hessians and the other German auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War, Harpers & Brothers, New York, 1884 [Download]

MAINE, H. C.: The Burgoyne Campaign, Troy Whig Publishing Co., Printers, Troy, N. Y., 1877 [Download]

“The retreat was a bad affair. Everybody was wet, tired and hungry. General Phillips said to Baroness Riedesel, who wanted to go forward as Burgoyne was halting at Dovegate, ‘What a pity it is you are not our commanding general.’ There is great significance in this censure of Burgoyne.

“The retreat was a bad affair. Everybody was wet, tired and hungry. General Phillips said to Baroness Riedesel, who wanted to go forward as Burgoyne was halting at Dovegate, ‘What a pity it is you are not our commanding general.’ There is great significance in this censure of Burgoyne.

“The Baroness was under fire from the Americans a good part of the way. After the army reached Saratoga the Americans under General Fellows fired cannon shot into their camp from a battery on the east bank of the Hudson.

“The Baroness and a number of her friends took refuge in the cellar of a house which is still standing. The heights about Burgoyne's camp were soon occupied and intrenched by the Americans in strong force, and Burgoyne's supplies were cut off. It even became dangerous to procure water and the army suffered greatly on account of insufficient food” (p. 50-1).

OSTRANDER, WILLIAM S.: Old Saratoga and the Burgoyne Campaign, Schuylerville, N. Y., 1897 [Download]

In “The Marshall Place”, as The Marshall House was known in the nineteenth century (even today some people in Schuylerville area call it in that way), Ostrander observes damages, yet preserved, suffered by the house during the cannonade from across the Hudson.

In “The Marshall Place”, as The Marshall House was known in the nineteenth century (even today some people in Schuylerville area call it in that way), Ostrander observes damages, yet preserved, suffered by the house during the cannonade from across the Hudson.

After alluding to the house as having been built by one Peter Lansing about 1770 Judge Ostrander describes the grim first night in the cellar:

“The cellar was divided by plank partitions into three apartments, into which the women, wounded officers and soldiers were distributed so as to occupy as little space as possible. Here, huddled together, amidst the cries and groans of the wounded, the darkness and damp of the cellar, and the stench of the wounds and accumulating filth, the night was passed in terror.

[…]

“The cannon ball which killed Surgeon Jones was probably fired from a little eminence across the river, not far north of Batten Kil[l]. It entered the northeast corner of the house and passed diagonally across the room since used as a parlor, thence through the thick plank partition of the hallway and on into the ground. One of these planks, which was cut and shattered at one end by the ball in its passage, is preserved upon the premises and shown to visitors. One of the rafters, cut partly in twain by a passing shell, was removed from its place in the frame while repairing the house in 1868, and is also preserved upon the premises.

“In digging for a small addition to the cellar in 1868, a small shot was found imbedded in the earth, which, from its position, is supposed to be the one which cut the rafter above. Several other shot and bits of shell ploughed up on the farm are shown. as is a large gold coin bearing the figure and inscription of George III, and on the reverse side the British arms and an inscription with the date, 1776. A curious old flint lock musket with bayonet, which was carried in the war by Abram [sic] Marshall, grandfather of the late William B., may also be seen.

“The huge pine beams overlying the cellar, one of the front doors of the ancient hallway, the piece of rafter and plank above described, and the curious, heavy front door lock which now protects the carriage house from light-fingered nocturnal travelers, are all as sound and well preserved as when the house was built more than a century ago. One of the partition walls of the cellar remains exactly as it stood during the cannonade. Another has been removed and the cellar bottom cemented. Aside from this it remains unchanged.

“The cellar as at present kept, light, clean and sweet, with rows of shining milk pans, heavy laden with thick cream, and its great fruit bins suggestive of rich harvest stores, seem spacious and inviting enough to lure the visitor to residence—and form a picture of the charms of peace, in strong contrast to the dark and bloody scenes of war enacted by the frightened people who crowded them a hundred years ago” (p. 31-34).

PALMER, HOLLIS A.: Leave it to the Ladies, Deep Roots Publications, Saratoga Springs, New York, 2006

“The couple talked for a few minutes trying to determine the best course of action […]. They grabbed the man by the legs and pulled his body through a small field and up to a barn full of hay […]. Scared and full of anxiety, the couple walked back to the Marshal[l] Place where Elizabeth had her room. Parker came inside and used a wash basin to clean the blood off himself as best he could.”

“The couple talked for a few minutes trying to determine the best course of action […]. They grabbed the man by the legs and pulled his body through a small field and up to a barn full of hay […]. Scared and full of anxiety, the couple walked back to the Marshal[l] Place where Elizabeth had her room. Parker came inside and used a wash basin to clean the blood off himself as best he could.”

At 7 p. m. of a warm day of July, 1916, Elizabeth Bain and Robert Parker killed Elizabeth’s husband, Peter Bain, close to a barn in the vicinity of The Marshall House. Elizabeth and Robert were actors in a love story, seeking to escape the tyranny of Peter, twenty years older than his wife, married to him when she was only sixteen.

In Leave it to the Ladies, Dr. Hollis A. Palmer reconstructs the crime and the consequent and sensational trial, widely covered by the press. Elizabeth was working in The Marshall House, and, in this very same place, both bloody lovers tried, unsuccessfully, to escape to their fate.

PEIXOTTO, ERNEST: A Revolutionary Pilgrimage, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1907 [Download]

Peixotto also has a place for the “Cellar in the Marshall House, Schuylerville, which was used as a Hospital by the British.” His drawing of the famed cellar again shows us how it looked like in the first years of the twentieth century.

Peixotto also has a place for the “Cellar in the Marshall House, Schuylerville, which was used as a Hospital by the British.” His drawing of the famed cellar again shows us how it looked like in the first years of the twentieth century.

“At the north end of his camp stood a house that had always belonged to the Marshall family. It still stands at the extreme north end of Schuylerville, quite in the open country, shaded by great pine-trees, and overlooking the placid Hudson. Its exterior has been modernized, so I have chosen to make a sketch of the cellar, the very one described by Madame Riedesel, the devoted wife who followed her husband, the German general, through this entire campaign and whose letters give so vivid an account of her Saratoga experiences. The rafters she describes, pierced by cannon-balls, can still be seen, and from the porch you may look across the river and see, as she did, the hills where the American soldiers stationed themselves to fire upon the house” (pp. 107-109).

Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, Vol. XII, New York State Historical Association, New York, 1913 [Download]

Between September 17th and 20th 1912, the New York State Historical Association held its fourteenth Annual Meeting in Saratoga Springs, Bennington and Schuylerville. The Association intended “to embrace every feature of Burgoyne’s Saratoga Campaign.” On a Friday, the members of the association took an 8.30 a. m. “special train” from Saratoga Springs to Schuylerville, where they held a meeting and rendered a visit to the Schuyler House.

Between September 17th and 20th 1912, the New York State Historical Association held its fourteenth Annual Meeting in Saratoga Springs, Bennington and Schuylerville. The Association intended “to embrace every feature of Burgoyne’s Saratoga Campaign.” On a Friday, the members of the association took an 8.30 a. m. “special train” from Saratoga Springs to Schuylerville, where they held a meeting and rendered a visit to the Schuyler House.

After a luncheon and several lectures on the roles of the generals Schuyler, Morgan and Arnold during the Battles of Saratoga, “the members visited the Marshall House.” Then, they returned to Saratoga Springs on another “special train.” These Proceedings include the Guide to Revolutionary and Colonial Sites at Schuylerville, copied “by permission” from J. H. Brandow’s Old Saratoga and The Burgoyne Campaign, (a book referenced above) in which this author relates the testimony of the “old man” who fought during the Battles of Saratoga, who revealed that the American patriots “supposed it [The Marshall House] to be Burgoyne’s headquarters.”

Mrs. Donald McLean writes a moved essay on the Baroness Riedesel, "born of distinguished parents; opulence was her birthright, and adulation her daily food." "No special mention is made in this monograph of Madame de Riedesel's experiences in the cellar of the old Marshall house to which cellar she retired with her children to escape the bombardment, and where she nurshed the wounded who had sought the same refuge, and shared with them her scanty provisions. This incident is so well known it seemed unnecessary to recapitulate" (p. 42).

REYNOLDS, CURLER (Dir.): Historical Exhibit of New York State at Jamestown Exposition, Norfolk, VA, April 26 - December 1, 1907, J. B. Lyon, State Printer, Albany, 1907 [Download]

The world fair celebrated in Jameston in 1907 commemorated the 300th anniversary of the founding of the first permanent English settlement in America. It included an exhibit of items and documents classified as New York State’s “Historical relics”, “Portraits”, “Maps”, “Prints in frames”, etc.

The world fair celebrated in Jameston in 1907 commemorated the 300th anniversary of the founding of the first permanent English settlement in America. It included an exhibit of items and documents classified as New York State’s “Historical relics”, “Portraits”, “Maps”, “Prints in frames”, etc.

One of the pictures shown in the exhibition was that of the “revolutionary house with an interesting story of its own, located on the hill west of the Hudson at Schuylerville, wherein Baroness Riedesel and many of Burgoyne’s officers and their wives found refuge at the time of the surrender in October, 1777, of which she wrote entertainingly in her published Memoirs.”

Escorted by the “Bible of Gen. Philip Schuyler of Albany”, a “Brick” from the original Saratoga home of General Schuyler, burned by General Burgoyne, and “a wooden canteen of [the] American army […] used in the Battle of Saratoga”, the exhibition showed several items related to The Marshall House.

In the section “Historical Relics”, the visitors could see a “Lock and its large Key, removed from the Marshall House at Old Saratoga (Schuylerville) where Burgoyne’s officers and Mme. Riedesel were quartered, October, 1777, week of the surrender.” This piece was owned “by Mrs. J [ennie] M [arshall] Sample, Schuylerville”, proprietor of The Marshall House at that time. In the present days, this “lock and its large key” secure the front door of The Marshall House having being reinstalled by Kenneth Bullard, father of present owner, David Bullard.

A second item related to the historic house was a “knocker”, though the story linked to it was erroneously associated with Baroness Riedesel’s refuge: “This old brass door-piece was in use upon the Marshall House door when Burgoyne and his officers dined there and the American from across the Hudson River shot the leg of mutton from off his table. Thereupon he held a council and it was deemed expedient to surrender.” That piece was owned at that time “by James Burton, Schuylerville” (p. 8).

Finally, also owned by Mrs. Jennie Marshall Sample, was exhibited a “cannon-ball, shot into the Marshall House at Schuylerville, during Burgoyne’s campaign, October, 1777” (p. 15). At present, several cannonballs found on the property are displayed in The Marshall House.

RIEDESEL, FREDERIKA CHARLOTTE: Die Berufs-Reise nach America: Briefe der Generalin von Riedesel auf dieser Reise und während ihres sechsjährigen Aufenthalts in America zur Zeit des dortigen Krieges in den Jahren 1776 bis 1783 nach Deutschland geschrieben, Haude und Spener, 1801 [Download]

Though the title suggests that this is a book by Baron Riedesel, it is actually the third edition of his wife’s journal, only preceded by a privately printed edition intended just for the family, and for the first widely distributed printed edition of 1800. This edition, which also includes letters that Baron and Baroness Riedesel interchanged with each other before their American journey, would be used for the first and incomplete 1827 translation into English.

Though the title suggests that this is a book by Baron Riedesel, it is actually the third edition of his wife’s journal, only preceded by a privately printed edition intended just for the family, and for the first widely distributed printed edition of 1800. This edition, which also includes letters that Baron and Baroness Riedesel interchanged with each other before their American journey, would be used for the first and incomplete 1827 translation into English.

RIEDESEL, FREDERIKA CHARLOTTE: Letters and Journals Relating to the War of the American Revolution and the Capture of the German Troops at Saratoga, translated from the original German by William L. Stone, Joel Munsell, Albany, 1867 [Download]

“The memory of Madame Riedesel will live in the hearts of Americans, as long as letters shall endure. The child-like trust in Providence, which alone enabled her to leave a luxurious home and powerful friends, and follow her husband across a pathless ocean into a strange land, then almost a wilderness, for the sake of sharing with him his trials and hardships, affords an example worthy of our study and admiration. Nor can any one peruse these touching records of a devoted, conjugal love, chastened and sanctified, as it was, by an unaffected religious experience, without the consciousness of a higher ideal of faith and duty.”

“The memory of Madame Riedesel will live in the hearts of Americans, as long as letters shall endure. The child-like trust in Providence, which alone enabled her to leave a luxurious home and powerful friends, and follow her husband across a pathless ocean into a strange land, then almost a wilderness, for the sake of sharing with him his trials and hardships, affords an example worthy of our study and admiration. Nor can any one peruse these touching records of a devoted, conjugal love, chastened and sanctified, as it was, by an unaffected religious experience, without the consciousness of a higher ideal of faith and duty.”

After several and incomplete tries to bring into English Baroness Riedesel’s letters, Stone’s translation becomes the ‘canonic’ version for the writings of ‘Mrs. General’, as the German lady was known in the British army and this edition names her from the very front page.

The book presents two interesting sketches (p. 128-129), one of the “present (1867) appearance of the house” before its embellishment one year later that brought it to its present character; the other one shows the cellar as it was in Stone’s time, revealing the central partition that divided that space as described by Baroness Riedesel in her journal (the second transverse wall that created the third cellar is not seen in this drawing.)

At page 129, first footnote, Stone identifies the “poor soldier” whose second leg was blown away by a cannonball while his wounded leg was being amputated, is identified by Stone as “a British surgeon by the name of Jones.” This “surgeon Jones” appears since then in every book written about the Saratoga Campaign as a real figure. Saratoga National Historical Park’s historian, Eric Schnitzer, has pointed out that there is no record of a British surgeon named Jones with Burgoyne’s army.

The passages that brought fame to the then little farm house are found between pages 127 and 134.

RIEDESEL, FREDERIKA CHARLOTTE: Letters and Memoirs Relating to the War of American Independence and the Capture of the German Troops at Saratoga, Translated from the Original German, G. & C. Carvill, New York, 1827 [Download]

In his canonical edition of Baroness Riedesel’s Letters and Journals, Stone points out that “a few and imperfectly translated portions of these letters were first published in English by General Wilkinson, in his Memoirs of my own Times, and were afterwards copied into Professor Silliman’s Tour in Canada. The work was subsequently more fully translated and given to the public in 1827. This translation, however, not only fails, in innumerable instances, to convey the ideas and spirit of the original, but omits nearly forty pages of the first and only German edition published in Berlin at 1800.”

In his canonical edition of Baroness Riedesel’s Letters and Journals, Stone points out that “a few and imperfectly translated portions of these letters were first published in English by General Wilkinson, in his Memoirs of my own Times, and were afterwards copied into Professor Silliman’s Tour in Canada. The work was subsequently more fully translated and given to the public in 1827. This translation, however, not only fails, in innumerable instances, to convey the ideas and spirit of the original, but omits nearly forty pages of the first and only German edition published in Berlin at 1800.”

This 1827 edition does not disclose the name of the translator from German into English. He was the Russian diplomat Jules Wallenstein, born in Hogar, in Prussian Silesia, and Russia's general consul in Brazil. Wallenstein admits in his edition: “For the passages which have been omitted, no apology will be required by those who can read the original. The reading portion of mankind has become so hostile to vulgarity, so delicate, and in some respects so fastidiously refined, that many things and words that were perfectly innocent and inoffensive, or only pervertible by the sagacity of profligates and ranks, at a time not distant from that of Fielding and Smollett, are now considered utterly disgraceful, and are wholly banished from polite literature.”

For instance, Wallenstein omits those two incidences where the Baroness discloses how she manages to change her linen in the extremely difficult circunstances of war. Stone rejects Wallenstein’s insinuations and stresses that “nothing” in these letters and journal “can offend the correct and cultivated taste of any true man or woman” in spite the “unstudied familiarity” in which they are written.

RIEDESEL, FRIEDRICH ADOLF: Memoirs, and Letters and Journals of Major General Riedesel during his Residence in America, translated from the original German of Max von Eelking by William L. Stone, Vol. I, J. Munsell, Albany, 1868 [Download]

RIEDESEL, FRIEDRICH ADOLF: Memoirs, and Letters and Journals of Major General Riedesel during his Residence in America, translated from the original German of Max von Eelking by William L. Stone, Vol. II, J. Munsell, Albany, 1868 [Download]

“Leifert, Feb. 22, 1776.

“Leifert, Feb. 22, 1776.

“Dearest Wife: Never have I suffered more than upon my departure this morning. My heart was broken; and could I have gone back who knows what I might have done. But, my darling, God has placed me in my present calling, and I must follow it. Duty and honor force me to this decision, and we must be comforted by this reflection and not murmur. Indeed, my chief solicitude arises from the state of your own health, in view of your approaching confinement. The care of our dear daughters, also, gives me anxiety. Guard most preciously the dear ones. I love them most fondly” (Vol. I, p. 30).

Baron Riedesel is ready to leave for America and is torn by concern for his pregnant wife, Frederika. In a time of marriages of convenience, the true love story between the Baron and the Baroness is portrayed in this collection of letters, in which military duty is mixed with the human nature of the Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel.

SINNICKSON, LINA: Frederika Baroness Riedesel, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. XXX, no. 4, 1906, pp. 384-408 [Download]

“One almost regrets that Fate decreed such a lovable and charming woman to be on the ‘other side’ in that struggle for so great a cause as American independence […] Great misery and disorder prevailed in the army, and in a house in which this accomplished and dignified woman sought shelter for herself and her children, she aided and assisted in the most sensible and direct way those poor, frightened, ill and wounded creatures, acting the part of an Angel-of-comfort among the sufferers, and ready to perform every friendly service, even such from which the tender mind of a woman might recoil” (p. 391).

“One almost regrets that Fate decreed such a lovable and charming woman to be on the ‘other side’ in that struggle for so great a cause as American independence […] Great misery and disorder prevailed in the army, and in a house in which this accomplished and dignified woman sought shelter for herself and her children, she aided and assisted in the most sensible and direct way those poor, frightened, ill and wounded creatures, acting the part of an Angel-of-comfort among the sufferers, and ready to perform every friendly service, even such from which the tender mind of a woman might recoil” (p. 391).

This biographical article reproduces the house and cellar sketches of the 1867 Stone’s edition of the Baroness journal and letters.

STEVENS, JOHN AUSTIN: The Burgoyne Campaign, an Address Delivered on the Battle-field on the One hundredth Celebration of the Battle of Bemis Heights, Anson, D. F. Randolph & Company, New York, September 1877 [Download]

During the celebrations of the first centennial of the failed Burgoyne campaign, Schuylerville was decorated with signs and ephemeral architecture marking the most important spots of the retreat and surrender of British army.

During the celebrations of the first centennial of the failed Burgoyne campaign, Schuylerville was decorated with signs and ephemeral architecture marking the most important spots of the retreat and surrender of British army.

According to Stevens account, “on the lawn, in front of the Marshall House, from a tall liberty pole floated the stars and stripes.” The Schuylerville Standard also recorded that tall pole and the big flag that the Marshalls put in front of the famous house. Of course, even more renowned was the house’s cellar. Stevens, founder of Sons of Revolution, also includes the text published by the local newspaper in that remarkable event.

“A hundred years ago from yesterday, in the cellar of the house, at present occupied by Mrs. Jane M. Marshall, there was a pitiful picture of a few crouching, terror-stricken women and children, and a number of wounded, hungry soldiers; a century later, yesterday, upon the lawn of the same house, there was a joyous, patriotic company of wives and maidens, raising into the air a liberty pole whereon, in a few days shall float the glorious emblem of freedom and victory.

“With dark memories of that house upon their minds did these women lift aloft with willing hands the celebrating staff of its peace and domestic love. The sad records of Madame Riedesel stand in dark contrast with this honorary act of Mrs. J. M. Marshall, Mrs. George W. Smith, Miss Jennie Marshall (the two latter the former’s daughters), Mrs. Chas. Bartram of Greenpoint, L. I., Mrs. Wesley Buck and Mrs. Joseph Hudson of this village. The pole is eighty-nine feet from the ground and will float a flag twelve by fourteen feet (p. 12).”

Stevens also records that “Mrs. Marshall also gave the two Albany companies of the Twenty-fifth Regiment, the day after the celebration, an elegant dinner set out on the lawn.”

The ‘Revolutionary tour’ of Schuylerville was massively followed by the crowd who assisted in the Centennial celebrations: “While the literary exercises at the stands were being held, thousands of people who could not get within hearing distance, amused themselves by strolling about the village and visiting the surrender grounds, the remains of old Fort Hardy, the Marshall House (in the cellar of which Mrs. Riedesel took refuge during the cannonade) and the ‘Relic Tent’ containing a sword said to have belonged to Burgoyne, the ‘Eddy collection,” and many other interesting trophies” (p. 20-1).

Jane M. Marshall figures as one of the subscribers of this memorial.

[Stevens’ text on The Marshall House was also reproduced in p. 238 of Centennial Celebrations of the State of New York prepared pursuant to a Concurrent Resolution of the Legislature of 1878 and Chapter 391 of the Laws of 1879 by Allen C. Beach, Secretary of State, Weed. Parsons & Co. Printers, Albany, 1879] [Download]

STONE, WILLIAM LEETE: The Journal of Captain Pausch, Chief of the Hanau Artillery during the Burgoyne Campaign, Joel Munsell’s Sons, Albany, N. Y., 1886 [Download]

Stone, translator and editor of Baroness Riedesel’s letters and journal, presents here the diary of one of the German soldiers under the command of General Riedesel. Though Captain Paush does not mention the Baroness, Stone opens the book with the famous sketch of the Baroness and includes as footnotes several quotations from the journal of Frederika Charlotte.

Stone, translator and editor of Baroness Riedesel’s letters and journal, presents here the diary of one of the German soldiers under the command of General Riedesel. Though Captain Paush does not mention the Baroness, Stone opens the book with the famous sketch of the Baroness and includes as footnotes several quotations from the journal of Frederika Charlotte.

The Baroness made herself iconic because of the calash (a small French Canadian horsed-drawn two wheel carriage) she used during the failed Burgoyne campaign. An aristocratic and young lady traveling in the middle of a massive movement of troops and escaping from the defeat of the army in a somewhat fancy carriage is an image that did not escape the many admirers of the wife of Baron Riedesel.

William L. Stone quotes a fellow historian who described a calash similar to the one Baroness Riedesel used during and after the Battles of Saratoga:

"’The Calash,’ says Weld, writing of his travels in Canada in 1795, ’is a carriage very generally used in Lower Canada; there is scarcely a farmer indeed in the country who does not possess one: it is a sort of one horse shay, capable of holding two people besides the driver, who sits on a kind of box placed on the foot-board expressly for his accommodation. The body of the calash is hung upon broad straps of leather, round iron rollers that are placed behind, by means of which they are shortened or lengthened.

“On each side of the carriage is a little door about two feet high, whereby you enter it, and which is useful when shut in preventing anything from slipping out. The harness for the horse is always made in the old French taste, extremely heavy: it is studded with brass nails, and to particular parts of it are attached small bells, of no use that I could ever discern but to annoy the passengers.

“Mrs. Riedesel, also, speaking of riding in a calash, gives her amusing experience with the driver of one of them ‘The Canadians are everlastingly talking to their horses, and giving them all kinds of names. Thus, when they were not either lashing their horses or singing, they cried, ‘Alons mon Prince! Pour mon general!’ oftener however, they said, ‘Fi, donc, Madame!’ I thought that this last was designed for me, and asked ‘Plait-il?’ ‘Oh,’ replied the driver, ‘ce n’est que mon cheval, la petite coquine!’ ‘It is only the little jade, my horse'” (p. 70, note I).

STONE, WILLIAM LEETE: Visits to the Saratoga Battle-Grounds (1770-1880), Joel Munsell’s Sons, Albany, N.Y., 1895 [Download]

Baroness Riedesel’s journal’s translator, William L. Stone, published in 1895 a recompilation of several early travels to Saratoga’s battlefield and its vicinity. One of the extremely interesting documents is the account of Philip Stansbury in September 1821. Stansbury was a native of New York City and obtained some celebrity at the time because of his walking tour of over 2,000 miles through New York, New England and Canada.

Stansbury relates that “a large farm-house stands upon a hill not far from the village, against which they kept up a terrible cannonade under the mistaken idea that in it all the generals were assembled. But it contained only wounded soldiers and the officers' wives, who had taken shelter from their destructive fire. Baroness Riedesel, with her infant children, being in the house, was obliged to seek refuge in the cellar, where she remained during a whole night, her children sleeping on the cold earth with their heads on her lap.

“This house was shown to me; it is called ‘Bushee's House,’ and remains still in a very good condition. [...]. The present tenants received me politely and pointed out the several rooms, rendered famous for the remarkable occurrences which transpired between these walls [...]. Strange stories are told about spots of blood which no washings could ever erase from the floor, but which, it appears, are at last hidden from sight by several coverings of paint.”

Stansbury was wrong about the boards being painted over the celebrated blood stains. In fact, the original flooring had been kept, and almost three-quarters of a century later Stone corrects Stansbury’s remarks: “Although the old house was remodeled about a decade ago, the greater part of it still remains as it was originally built. The flooring of yellow pine plank, fifteen inches wide, and held in place by wrought iron nails, is still to be seen, upon which the blood stains of the wounded soldier who was struck by a cannon ball are visible.”

Stone shows his knowledge of the history of The Marshall House in a four-page note, in which he refers to Jane M. Griswold, William Marshall’s widow (Bushee’s son-in-law’s widow) as “the present (1894) owner of the house who is one of the most patriotic ladies of the day, and who takes great pride in her possession” (pp. 176-181).

General Epaphras Hoyt, another traveler and also an historian of the American Revolution, mentions the The Marshall House at the time of his 1825 visit: “After a short respite at the stage-house in Schuylerville we prepared for a reconnoisance of Burgoyne's camp, which extended along the heights from Lemson's, now Bushett's [sic] house, the same occupied by Madame Riedesel [...]. Bushett's house, near the left of the German camp, in which Madame Riedesel had her quarters while the British army lay at this place, has been repaired by its present owner, and he informed me that the marks of the cannon balls mentioned in the narrative of that lady were to be seen when first occupied by him.

“The American battery from which the house was cannonaded was planted on the opposite bank of the Hudson above the mouth of the Battenkill. It is justly due to the officer who directed the fire, the Hon. Maj.-Gen. Ebenezer Mattoon, and since adjutant-general of the militia of Massachusetts, then a lieutenant in the artillery, to state that the unfortunate condition of the people in the house was unknown, and that it was supposed to be the quarters of some of the enemy's general officers” (pp. 202 and 210).

Other travelers –the English gentleman James Stuart, for instance-, also visited the house. Stone points out that in the last years of the 19thCentury “the cellar in which Mrs. Riedesel took refuge, with her children, during the cannonade from Fellows' batteries, is kept in excellent condition by Mrs. Marshall, who lives in the house and takes patriotic pride in its possession” (p. 306).

SYLVESTER, NATHANIEL BARTLETT: History of Saratoga County, New York, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers, Everts & Ensign, Philadelphia, 1878 [Download]

Seminal work about Saratoga County, with a massive quantity of detailed references to its inhabitants and events. The Marshall House is present in many places in the book, both by itself, as an historic landmark, and also in its references to the genealogy, personalities and businesses of the Marshalls (p. 261, 283-4) and Bullards (pp. 265 and 282-3), the only two families who have dwelt in the house for two centuries.

Seminal work about Saratoga County, with a massive quantity of detailed references to its inhabitants and events. The Marshall House is present in many places in the book, both by itself, as an historic landmark, and also in its references to the genealogy, personalities and businesses of the Marshalls (p. 261, 283-4) and Bullards (pp. 265 and 282-3), the only two families who have dwelt in the house for two centuries.

In the map shown between pages 66 and 67, “Plan of the Position which the Army under Lt. General Burgoyne at Saratoga on the 10th of October, 1777 and in Which it Remained till the Convention was Signed”, The Marshall House -at that time known as the Lansing House (p. 263)- is shown upon its hill.

The description of the battle states that “the Hessians under Riedesel were located on the ridge extending northerly towards the Marshall House, and the artillery was on the elevated plain extending between the Hessians and the river flats” (p. 66).

Albert Clements, from Victory, related that “he has heard Abram [sic] Marshall [the first Marshall in Schuylerville] say he saw Burgoyne deliver his sword to General Gates, - that the place was south of the Gravel hill, near the old Dutch church.”

Sylvester’s work also includes a full page splendid sketch of William B. Marshall and Jane M. Marshall, the owners of The Marshall House in 1878, along with two drawings of the building, one of the old house that sheltered the Baroness Riedesel and the rest of women, children and wounded personnel for almost a week after the defeat of the British army before its surrender, the other a sketch showing the house after its renovation.

The house remains substantially unchanged since. Jane and William Marshall respected the essential character of the old building and, of course, its original and famous cellar.

The Tile Club Afloat, Scribner’s Monthly, Vol. XIX, no. 5, March, 1880, pp. 641-671 [Download]

The Tile Club was a group of American artists that existed from 1877 to 1887. Winslow Homer, John H. Twachtman, Elihu Vedder, William Merritt Chase, Augustus Saint Gaudens and Arthur B. Frost were some of its members. United by its love of the decorative arts, the group made several “expeditions” for artistic profit. In 1879 the “Tilers” rented a boat to cruise New York’s canals. They put in at Schuylerville where they first paid a visit to The Marshall House and then to the Schuyler House.

The Tile Club was a group of American artists that existed from 1877 to 1887. Winslow Homer, John H. Twachtman, Elihu Vedder, William Merritt Chase, Augustus Saint Gaudens and Arthur B. Frost were some of its members. United by its love of the decorative arts, the group made several “expeditions” for artistic profit. In 1879 the “Tilers” rented a boat to cruise New York’s canals. They put in at Schuylerville where they first paid a visit to The Marshall House and then to the Schuyler House.

The following is the account of what “The Tilers” saw and felt in the house of the “German angel”:

“In the mansion where for several nights Baroness Riedesel was bombarded by the Americans, the artists were shown the cellars where the fugitive lady lived so long in terror; the Continentals kept up an industrious fire upon it, under the impression that it was the castle of the British generals, instead of the refuge of a gentle woman.

“In those basements the fair dame played the part of a veritable angel –a German angel. With one hand she made soups for the wounded who were brought in; with the other she covered the mouth of her screaming little Frederika, the child who safely grew up to be the Countess von Reden and the friend of Humboldt.

“In this sad cavern the recording stylus of history still shows its legible penmanship; the beam or rafter stretches near the cannon ball that shattered it, above the floor on which the anxious mother counted the hours of the night, sitting on the ground with her children in her lap; and a sovereign of 1776, dug from the earth, perhaps a bit of the British gold that paid her Hessian husband, is exhibited, with the usual tomahawks and flintlocks of this sort of museum” (p. 659).

WALWORTH, ELLEN HARDIN: Saratoga. The Battle-Ground Visitor’s Guide with Maps, American News Company, New York, 1877 [Download]

This, at its time, well known ‘tourist guide’ walks the reader through The Marshall House, recalling how, after Burgoyne’s defeat, “the sick, wounded and women were huddled together in a house where cannon balls tore through the walls, and rolled across the floor, often wounding the helpless men who lay within.” “Madame Riedesel, with her children, and other ladies took refuge in the cellar, where hours of horror were endured with uncomplaining misery”, adds Walworth (p. 31).

This, at its time, well known ‘tourist guide’ walks the reader through The Marshall House, recalling how, after Burgoyne’s defeat, “the sick, wounded and women were huddled together in a house where cannon balls tore through the walls, and rolled across the floor, often wounding the helpless men who lay within.” “Madame Riedesel, with her children, and other ladies took refuge in the cellar, where hours of horror were endured with uncomplaining misery”, adds Walworth (p. 31).

In the course of a visit to Schuylerville, a fictional dialogue shows the tragic appeal of The Marshall House to visitors: “Colonel Shelby: […] ‘There was some skillful cannonading there by the Americans for a few days before the surrender, and it is where Madame Riedesel spent those dreadful nights in a cellar.’ Miss Pelham: ‘Don’t tell me anything about that. Battles are quite grand in the abstract, but I don’t like the particulars’” (p. 64).

Walworth takes the Saratoga Revolutionary tourist to what she calls “the Riedesel house, now owned by Mr. Marshall, and shown to visitors with great kindness, and intelligent interest.” “This house was visited by Mr. Lossing nearly thirty years ago, when he sketched the interior and exterior for his Field Book [also, in this website]. Since then the house has been remodeled, but the main timbers, and, in fact, all the rooms remain as they were in 1777.

“The rafter and base boards, through which the cannon balls passed, have been removed. They are carefully preserved, and upon inspection, will be found to authenticate Madame Riedesel’s thrilling account of the days spent in this house; scenes that are vividly recalled as one stands upon the cellar floor, where her little children crouched in terror (p. 74).”

WOOD III, THOMAS N.: Saratoga, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2010 [Download]

This postcard collection of Old Saratoga –Schuylerville- and the new one, Saratoga Springs, includes pictures of the Baroness Riedesel (p. 11), who “nursed the wounded British officers in the cellar of the Marshall House”, and of the former Dutch Reformed church parsonage throughout the Revolutionary war (p. 30), whose “knocker on the door was in use on the Marshall House in 1777.”

This postcard collection of Old Saratoga –Schuylerville- and the new one, Saratoga Springs, includes pictures of the Baroness Riedesel (p. 11), who “nursed the wounded British officers in the cellar of the Marshall House”, and of the former Dutch Reformed church parsonage throughout the Revolutionary war (p. 30), whose “knocker on the door was in use on the Marshall House in 1777.”

Three splendid views of The Marshall House are shown in p. 27-8. Wood states that renovations since the Revolutionary War “have only slightly altered its appearance” and that “the splintered beams and other relics are well preserved in the structure.”

MOST REMARKABLE CONTEMPORARY BOOKS RELATED

TO BARONESS RIEDESEL AND THE MARSHALL HOUSE

BROWN, MARVIN L. [Ed.]: Baroness on the Battlefield, American Heritage Publishing Co., 1964

BROWN, MARVIN L. [Ed.]: Baroness Von Riedesel and the American Revolution: Journal and Correspondence of a Tour of Duty, 1776—1783, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1976

KETCHUM, RICHARD M.: Saratoga, Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1999

THARP, LOUISE HALL: The Baroness and the General, Little, Brown and Company, Boston – Toronto, 1962 [Download]